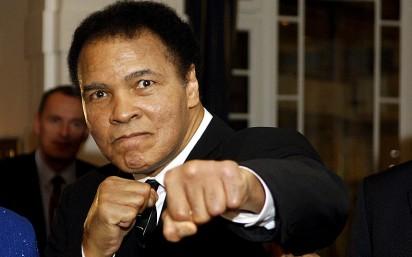

Ali

By Douglas Anele

The unprecedented number of tributes to the greatest sportsperson of all time, Muhammad Ali, who died earlier this month might create the erroneous impression in certain quarters that enough has been said about this remarkable human being such that there is no need for more eulogies at this time. But given Ali’s phenomenal achievements not just as an athlete but also as a civil rights activist and philanthropist, people will continue to talk about him for a long time to come.

In fact, I am convinced that the supremely self-confident young Cassius Marcellus Clay who declared himself the greatest boxer that ever lived after knocking out Sonny Liston in 1964 to win the heavyweight boxing championship of the world was to boxing what Albert Einstein was to physics and Bertrand Russell to philosophy. Virtually everyone who followed his boxing career until he finally retired in 1981 would concur that he was the most handsome and most humane pugilist in the world. Therefore, it is proper that Ali’s funeral ceremonies were beamed live to a global audience through cable television. Now, as I watched and listened with rapt attention former President Bill Clinton and others pay tribute to the fallen hero, I was surprised that hot tears started flowing from my eyes. My admiration for Muhammad Ali began in 1974 after he knocked out George Foreman to regain the heavyweight boxing title stripped from him seven years earlier for refusing to fight in the Vietnam War. It was consolidated after the veteran sports journalist, Chuka Momah, through his television series, brought the greatest fights of Ali into the homes of Nigerians. The title bouts of Mohammad Ali that made the greatest impact on me were the ones he described eponymously as the “Rumble in the Jungle” and “Thriller in Manila.” I have watched both fights so many times on ESPN such that I can see in my mind’s eye at anytime the most incredible display of boxing intelligence by any fighter ever.

From 1964 to 1981, Ali made heavyweight boxing a highly respected sport worldwide, despite the brutality, blood, pain and possibility of serious head injuries and death associated with pugilism. Millions of people who hated boxing or were indifferent began to like the sport because of the man who “floats like a butterfly and stings like a bee.” Muhammad Ali revolutionised boxing with his incredible skills, resilience and mesmerising footwork while in the ring. Ali did what no previous boxer before him had done: he predicted the round in which he would knock out his opponents – and he was right most of the time. For Ali, boxing is a “sweet science” or, more accurately, a harmonious combination of science and artistry. For boxers like Sonny Liston, Joe Frazier, George Foreman and, much later, Mike Tyson, boxing is all about overwhelming your opponent with menacing stares, powerful punches and brute force. But Ali’s style was deliciously different. To begin with, he saw boxing as a sport with soul, rhythm and poetry, a matter of more brain and less brawn. This is amply demonstrated in his brilliant poems and witticisms. Second, before a fight (and on several occasions when the fight was still on) Ali would taunt and talk to his opponents. This is as much a defence mechanism as it is an attempt to boost self-confidence in himself. Third, Ali had the fastest pair of hands in any category of boxing: those quick hands, in my opinion, constitute one of the most lethal weapons in his boxing arsenal. Most crucially, Muhammad Ali was the master of boxing improvisation. The rope-a-dope strategy he deployed to neutralise the awesome punching power of George Foreman before knocking him out in the eighth round is a textbook example of how a thinking but less powerful fighter can overcome a more deadly puncher, although afterwards Foreman and his crew gave flimsy excuses as to why he lost. Moreover, the unbelievable brutality of “Thriller in Manila,” a confrontation in which Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier pummelled each other until the latter could not come out for the fifteenth round demonstrated that Ali was one of the most resilient boxers the world has ever known. Some commentators argue, and plausibly too, that the fight in Manila was partly responsible for the poor health suffered by both men in later years. Still, most boxing historians would rank it as one of the greatest boxing events in history.

In his tribute to “The Greatest,” George Foreman stated that restricting Ali’s greatness to his boxing career is an injustice. Most people would agree with that proposition. Indeed, if Ali were a philosopher, he would likely be a theistic existentialist. Like all genuine existentialists, Ali affirmed his authentic individuality by sticking to his principles even when it was unpopular to do so. As already indicated, he refused to join the United States army and fight in Vietnam War because, according to him, he has no quarrel with any Vietnamese, and none of them had called him a nigger. He paid dearly for his decision. Nevertheless, he remained resolute until the US Supreme Court annulled the withdrawal of his boxing license, which enabled him to return to the ring once again. Remarkably, in a society where Islam is anathema for millions of people, “The Greatest” converted to the religion and changed his name to Muhammad Ali from his slave name, Cassius Marcellus Clay. This singular rebellious act is not just an affirmation to be who he wanted to be, it is a poignant rejection of the domineering white supremacist establishment that professed Christianity and, yet, supported the most atrocious racial discrimination of the twentieth century. Evidently, Ali lived by his own principles on his own terms in order to justify his unshakable belief in the beauty, resilience and dignity of the black person. In affirming his authentic black individuality, “The greatest” transcended his blackness and boxing, which provided him the platform for the incredible influence he had on people worldwide. He made an impact as a diplomat, humanitarian and as an ambassador of peace globally. In his hometown, Louisville, Kentucky, ordinary people testify to his kindness, his humanity and humour. No one in any sport truly deserves the title “The People’s Champion” more than Muhammad Ali does.

Ali’s greatness was also evident in the way he lived with dignity and grace despite his affliction with Parkinson’s disease. Overall, he endured his illness with stoic equanimity, although sometimes the boxing genius vented his frustrations on close family members and relatives. That is quite understandable. In his heydays as a boxer, Ali was the epitome of wit, quickness, loquacity and strength: to be weighed down by an incurable health challenge after such a glittering boxing adventure would have broken ordinary mortals. But, true to his heroic nature, iron will and determination, Ali did not indulge in self pity or regret taking up boxing as a career. His attitude is an inspiration to all those living with one health issue or another.

Like all geniuses, Ali did not pay adequate attention to raising a stable family. As an incredibly handsome and wealthy boxer, many women must have been soliciting for his attention – it would be unrealistic to expect him not to succumb occasionally. Ali married four times: some of his relationships took a heavy toll on his private life. Children of great human beings rarely achieve the eminence of their parents. “The greatest” was not an exception: his only son, Muhammad Ali (Jnr.), is an obscure fellow who sometime ago was reportedly living in poverty whereas one of his daughters, Leila Ali, is a talented boxer who can never get to the level her father achieved in boxing.

Muhammad Ali was a giant among giants. If Ali had lived about seven thousand years ago, he would have been worshipped as a God because he personified the Platonic Form of Boxing, and the inexhaustibility of inspiration that flows from his life places him in the pantheon of immortals. The best those of us who admire Ali can do is to live “dangerously,” that is, authentically, and remain true to who we are and what we believe in, knowing full well that one day we must die. We should stop counting the days and start making the days count. My sincerest condolences to the family and close relatives of the greatest sports personality of all time, Muhammed Ali.

Disclaimer

Comments expressed here do not reflect the opinions of Vanguard newspapers or any employee thereof.